If you own a home and your lender says flood insurance is required, you may feel stuck. The good news is that a fema elevation certificate can sometimes change that outcome. In the right situation, this document can show that your home sits higher than the risk level shown on flood maps. As a result, flood insurance may become optional instead of mandatory.

Why flood insurance gets required in the first place

Flood insurance rules often feel confusing. Most lenders rely on FEMA flood maps to decide if a property needs coverage. If your home falls inside a mapped flood zone, insurance becomes mandatory for a mortgage.

However, these maps show risk by area, not the exact height of your home. That difference matters. Many homes sit on higher ground than the map assumes. Others were built before maps were updated. Because of that, some owners pay for flood insurance even when their actual flood risk is low.

This is where an elevation certificate becomes useful.

What a FEMA elevation certificate really shows

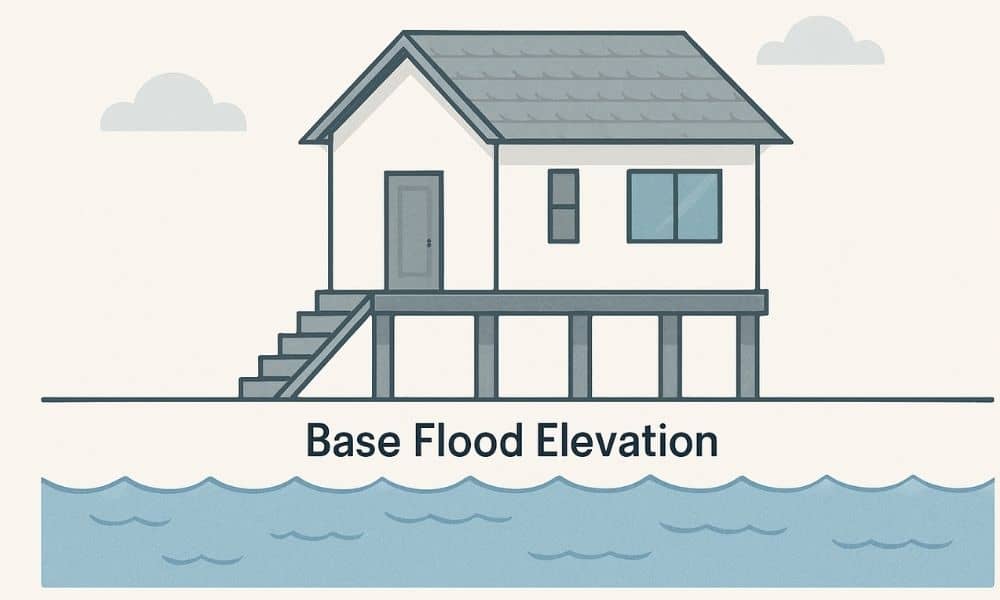

An elevation certificate is not just a form. It is a technical document prepared by a licensed land surveyor. It shows how high your home sits compared to the Base Flood Elevation, often called the BFE.

The BFE is the estimated height floodwater could reach during a major flood. FEMA uses it as a benchmark. Your elevation certificate compares key points of your home—especially the lowest floor—to that benchmark.

In simple terms, it answers one question: Is your home built above or below the expected flood level?

If the answer is “above,” you may have options.

When an elevation certificate can remove mandatory flood insurance

Not every homeowner qualifies, so clarity matters. Flood insurance can sometimes be removed only when the elevation certificate proves that the structure sits above the BFE.

This situation often applies to:

- Homes near rivers or creeks that never flooded

- Older houses built before newer flood maps

- Properties on small rises or higher lots within a flood zone

- Homes flagged during refinancing or sale

When the elevation data shows your lowest floor is higher than FEMA’s flood level, you can request a formal review. At that point, the certificate becomes evidence, not just paperwork.

Using an elevation certificate to qualify for a LOMA

To remove the insurance requirement, most homeowners must apply for a Letter of Map Amendment, also known as a LOMA. This letter officially updates FEMA’s records for your specific property.

Here’s how the process works in real life.

First, you confirm your current flood zone using FEMA’s official map tools. This step helps you see why insurance is required.

Next, you hire a licensed land surveyor to prepare a FEMA-compliant elevation certificate. Accuracy matters here. FEMA and lenders reject estimates, outdated data, and non-certified work.

After that, you submit the elevation certificate to FEMA as part of a LOMA request. FEMA reviews the elevations, compares them to the flood map, and decides whether the property truly sits above risk level.

If FEMA approves the request, they issue the LOMA. At that point, lenders usually remove the insurance requirement. Flood insurance then becomes optional, not mandatory.

How an elevation certificate can lower insurance costs even without a LOMA

Sometimes flood insurance stays required. Even then, an elevation certificate still helps.

Insurance pricing depends on risk. Without elevation data, insurers assume worst-case conditions. With proper documentation, they can price coverage based on real elevation instead of assumptions.

As a result, many homeowners see:

- Lower annual premiums

- More policy options

- Fewer surprises during renewals

While savings vary, documented elevation often leads to fairer pricing.

Common mistakes that cost homeowners time and money

Many owners give up because they run into problems early. These issues often come from misunderstanding the process.

One common mistake is ordering an elevation certificate after closing on a loan. At that point, leverage is gone. It works best during refinancing or before final underwriting.

Another issue involves using old certificates. Elevation certificates expire when flood maps change or site conditions shift. Outdated forms often trigger rejections.

Some homeowners also rely on unofficial measurements. Unfortunately, FEMA only accepts certificates prepared by licensed professionals using approved methods.

Finally, many people skip FEMA’s map tools. Without confirming eligibility first, they apply for a LOMA that never had a chance.

Why properties face unique flood map challenges

Minneapolis has its own set of factors that affect flood risk.

Snowmelt plays a major role. Water levels rise quickly in spring, even without heavy rain. At the same time, urban drainage systems continue to evolve. Improvements do not always show up on older flood maps.

Additionally, many neighborhoods sit near rivers or low corridors that FEMA mapped conservatively. In practice, actual elevations may be higher than assumed.

Because of these conditions, elevation certificates carry extra value in this region. They help separate real risk from mapped risk.

Is an elevation certificate worth it for your property?

The answer depends on your situation. Still, certain signs suggest it may help.

If flood insurance feels unnecessary, or premiums seem high, documentation can bring clarity. The same applies if insurance requirements appear suddenly during refinancing or sale.

Elevation certificates work best when homeowners want facts instead of assumptions. They provide a clear picture of risk and open doors to options that maps alone cannot offer.

Final thoughts:

A FEMA elevation certificate is not a guarantee. However, when used correctly, it becomes a powerful tool. It can support a LOMA request, reduce insurance costs, and protect property value.

For homeowners, the key is understanding when the certificate works and how to use it strategically. With the right approach, flood insurance decisions become clearer, fairer, and more manageable.

If flood insurance feels like a permanent burden, elevation data may tell a different story.